Shaping the Foils that Re-Shaped The America's Cup: Part 2

ETNZ Designer Gino Morrelli (and Pete Melvin)

See Part 1

September 18, 2013

Emirates Team New Zealand in America's Cup Race 11, September 18. Image:©2013

Chris Cameron/ETNZ

Gino Morrelli, Pete Melvin's partner at Morrelli & Melvin Design & Engineering, talks about M&M's development of foiling multihulls, how Emirates Team New Zealand's foils work, and how the technology is already transferring to other yacht racing from the America's Cup:

Gino Morrelli puts some numbers to the AC72: “It’s a 72-foot, 45-foot wide, 12,000-odd-pound beast that can fly a hull in about 6 knots of wind, and can fully go airborne like this in about 10 or 12 knots of wind.”

Top-end speeds over 50 mph have been flashed in racing, documented on LiveLine telemetry. “It can do that in about 20-something knots of wind, so it’s about a 2-point-something windspeed boat,” says Morrelli.

As fast as a wingsail multihull is, a foiling cat is faster. Getting the boat up on foils and keeping has become key to winning the 2013 America’s Cup.

With foils it takes about 10-12 knots of wind to fly barely, 16-18 knots to fly fully. The payoff for getting an AC72 up on foils is immediate, boat speed jumps by about 5 knots at the low end when the leeward hull gets airborne, and the gain at the top end can be twice that or more, with top speeds going from the 30-plus knot range into the 40s and edging toward 50 knots. Foiling has changed the game.

The Foils

|

|

| The AC72 daggerboards must be no

larger than 7 meters/22-ft 11-inches in any direction (Rule 9.3).. Photo:©2013 ACEA/Gilles Martin-Raget |

“These are the really weird curved daggerboards we’ve been developing. They’re what really ... the whole game is about,” says Morrelli. As for the hulls, “We call them a ‘board-delivery device.’ They barely even touch down even during tacks and gybes.”

A few smaller boats have effectively used lifting foils in the past, such as the Moth dinghies, and in the last few years the A-Class catamarans, but fully flying a large multihull on foils was rarely done except for isolated situations.

“The French had been playing with foils for 15 years, foil stabilized,” Morrelli says. "But they were still basically sailing on the main hull, leeward hull being lifted, but not trying to fly the whole boat, except for boats like Hydroptère which are completely other animals. We’ve been following some of those trends and some of those trends have been dictated by carbon rigs and carbon sails, because we didn’t really have the power to get the boats out of the water until engines got better.”

Upgrading the engines took improving multihull designs in all areas, including the structural platform, the rigging, and the control systems.

“The problem has been in the past -- even with Kevlar sails -- they are too elastic and our boats are so stiff in righting moment, that to get the hull out of the water you’ve got to translate all that power through the rig, through the shrouds and the mainsheet, to get the boat out,” says Morrelli. “And if the rig is twisting and flexing to get the boat out, then you are giving up that power and the boat doesn’t come out of the water. So it’s been the evolution of sail development, and lines, hydraulics, to translate the power back into the platform. Now we have plenty of power and now we can lift the boat out of the water.”

Having the power to fly is one thing, having the ability to control a foiling cat was another feat completely in the America's Cup.

AC72’s on foils are “dynamically supported,” where the motion of the water over the foils creates the lifting forces that elevate the hull out of the water. That sounds straightforward, but it cuts both ways. Foils come with inherent issues, including that as speed increases, lift increases, which can make the foils themselves rise to the surface of the water and suddenly lose effectiveness, setting off a sequence of losing support, dropping back down, slowing, and then accelerating again to repeat the inefficient cycle. Or if the boat gets out of hand, for example, the angle of attack can increase too sharply, shooting the bows skyward while dropping the transom. Out of control is not a recipe for winning.

How to do it

It’s obviously critical to control the angle of attack of the daggerboard foils, letting the crew adjust the board to suit speed, angles, and wind conditions. The goal is to sail the boat in a steady balance and let speed build, to say nothing of just keeping the boat upright and intact. There is just one problem, though; the rules don’t allow the crew or an onboard system to actively adjust the angle of attack of the foils when the boat is racing. The Rules also don't allow any adjustment of the foil angles on the rudders during the race. The daggerboards can be raised and lowered while sailing, but under the AC72 Class Rule there are strict limits on managing the boards.

Pete Melvin, who with Morrelli and their staff authored the AC72 Class Rule, explains the restrictions: “In the rule, you are allowed to adjust rake and you’re allowed to adjust cant. The rule also states that you can’t move the lower bearing but you can perform any sort of rotation you want. So there’s a possibility that if you had, say, a trim tab on your daggerboard, you could control lift that way and it would require far less power and force to actuate that than to move the entire board. But when we were working on the rule, our group thought that limiting moving parts on the foils would reduce cost and complexity, but possibly that was a mistake. If we’d known these boats would be fully foiling, there could have been a better solution.”

In the tradition of unintended consequences, the AC72 Class Rule was written this way to control costs and promote healthier designs, but created a huge technical challenge for the design teams.

The Class Rule actually started out differently in draft form. Morrelli says: “Oracle let us write a rule that said there was unlimited development of the foils; you could have flaps; you could tweak your rudder; you could have active controls; you could have a wand dragging in the water like a Moth, the sailing dinghy. It was basically open game, there were no rules. Whatever you brought that could fit in the box, you could run.”

But the Class Rule is the product not just of designers. The Class was shaped by a meeting of the minds between the Defender and the Challenger of Record, who at that point in time was Club Nautico di Roma, represented by Mascalzone Latino. Compromise was involved.

“The Italians vetoed that extreme open example because they thought it was too expensive,” Morrelli says. “It would be detrimental to the Cup developing boats that were reliable, and they squashed it.”

The performance potential of lifting foils was too great to be left untapped, though. The question became how to control an AC72 catamaran on foils within the AC72 Class Rule. Smaller boats can rely on crew movements fore-and-aft to achieve stable flight on foils, but the AC72’s were too big for that approach, so more creative solutions were necessary.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“That left designers with a problem of trying to find ‘how do we fly it without flying the boat?’ It’s not like an airplane, you have a stick, and you can change the rudder and the ailerons,” Morrelli says. “We basically had to build a boat that was self-flying, because there was very little opportunity to articulate the boat without sensors.”

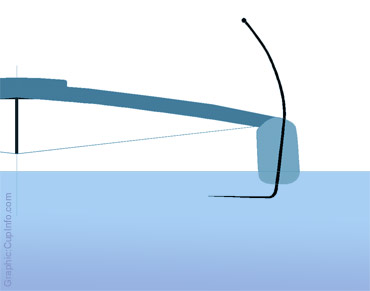

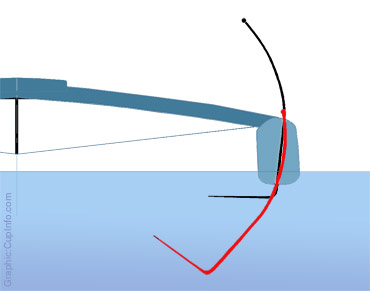

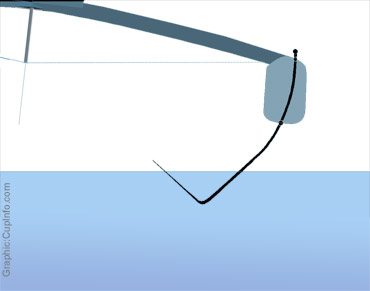

Emirates Team New Zealand’s technique is to attach their foil to an curved daggerboard. When the board is lowered, the meeting of the extended foil and the rest of the board forms a ‘V’-shape instead of an ‘L.’ The ETNZ boat sits on the ‘V’ so that when boat speed increases, and lift increases, the foil rises higher in the water with both legs of the ‘V’ at an inclined angle instead of nearly horizontal.

“The advantages/disadvantages are this ‘V’ is self-leveling,” Morrelli says. “As it raises up to the surface at high-speed, it loses lift, because it stalls a little bit, and it settles back down -- where a true ‘L’ will go completely out of the water, and you have to find another way of controlling the angle of attack and the amount of lift it creates.”

Because the foils extend to their tips at an upward angle instead of flat, as the foil reaches the surface the portion of the foil with water flowing over it, generating lift, is reduced incrementally, and the boat comes down gradually to an equilibrium point. The idea is to balance the forces as speed changes, avoiding the all-or-nothing conditions that a more horizontal lifting foil encounters.

It’s not the only solution for an AC72, but for the pragmatic New Zealand team, it seems to fit.

“There are these ways that people are trying to control their daggerboards with almost like car-like suspension systems,” says Morrelli, noting that those alternatives bring penalties in weight and complexity. “We’ve opted for this.... It’s a rather simple, robust system of flying our boat.”

“In the upwind position, by having articulating bearings at the deck and the bottom, we can put our foil basically vertical when we want lots of lateral resistance, lot of side force and not so much lift. In light air we can actually rake the board back and take the angle of attack out of it, so it’s not lifting very much. It’s draggy, but it’s not lifting.”

Development

Morrelli & Melvin’s experience with foiling actually goes back to power boats, where as long as power is sufficient, the decision to foil is primarily a calculation about saving fuel costs. But adapting foils to multihull sailboats has been series of explorations, first in development classes like the A-Class cats and then in limited production boats.

“We started with A’s probably 5-6 years ago,” Morrelli says. “Then we started playing with the Nacra 20, that’s about five years ago, and that was the first production attempt at building a 20-foot boat -- a carbon boat with curved foils and carbon rig -- and it’s been pretty successful. From that we moved to the SL33 and the F17 in the years after that.”

As a platform for foil development, and to give their crews hands-on experience, Emirates Team New Zealand used a pair of Morrelli & Melvin-designed SL33's. “We actually designed [the SL33] a year before the Cup even went to catamarans, so it was only fortuitous that we had a boat already designed and already under construction. We were building then in New Zealand just by chance.”

“We did most of our daggerboard experiments on these boats because they were easy to do and cheap to do, relatively,” says Morrelli. “A daggerboard on one of these is about a five-grand, eight-grand problem. A daggerboard on our AC72's? A pair of boards is $400,000. So we didn’t want to make many of those.”

America’s Cup teams are limited to building 10 boards for the big boats, but as long as the test platform is a boat under 10 meters, there’s no limit on the number of daggerboards that can be tried.

“So we made lots of these,” Morrelli says, referring to the

SL33 boards. “We can build these in the shop, and whack them off and

change them. So that’s where we’ve developed to. The boats are very

fast, flying downwind now on foils very steadily.”

Note daggerboard tip above surface at right. Image:©2013 ACEA/Photo: Ricardo

Pinto

Center of Effort

Foil development was also a function of time factors and the nature of attacking the AC72 design problem within the context of the America’s Cup. The teams were allowed to build two boats, 4 wingsails, and 10 daggerboards/foils, but the lead times for design and building make it impractical to feed very much real-world data back into major changes to the hulls and wing sails. The first boat by rule couldn’t even be launched until about a year before Louis Vuitton Cup competition started. ETNZ was the first team with an AC72 in the water and they still had to commit to the design of the second of two AC72’s just weeks after the boat #1 got wet. The schedule let them validate their first design in a general sense, but not spend a lot of effort to test and optimize on a large scale, let alone explore concepts that were more radical.

Even if the teams were not restricted by rule in the number of hulls and wingsails that they could build, and even regardless of budget, there simply isn't the capacity to build and deploy enough iterations in a short enough time to take advantage of a methodical step-by-step development program for all major components. The end result is that the AC72 hulls and wings have to be good enough, subject to minor modifications, but not perfect, and a lot of the performance deltas in Louis Vuitton and America’s Cup racing come from boathandling, maneuverability, and foiling performance.

That means a lot of resources funneled into the boards. And even with all the design ingenuity at hand, the foils run into limitations of physics.

“It becomes a material science problem,” Morrelli says. “We’re building those things as thin and as deep as humanly possible given our level of technology and understanding. They’re pretty much solid carbon, but the way we build them, the way they are manufactured under high intense heat and pressure, it’s really the most aerospace part on the boat, is the daggerboards.”

“They take about three months to build, once we have a set of tools. They are super labor-intensive.”

There appear to be differing schools of thought when it comes

to building daggerboards, though. “In fact, we were shocked when Oracle’s

broke,” Morrelli says. “The first day sailing they broke one of their

daggerboards and it popped up and it floated away.” That’s not what the

ENTZ guys would have expected. “Ours would sink like a stone ... and be down in

18 feet of mud.”

Testing and Development in the AC

With a lot left to learn, and the ability to keep drilling into the foil problem, teams were building and testing them even into this summer as racing was underway.

Foil development was always expected to keep going, probably

going on until the last second Morrelli says. “How small can we make it

and fly upwind? And compare it to a boat that’s got an 80% lift fraction

as opposed to 100%, work it back to an 80% boat, and test the delta between

those two extremes.”

Trickle Down

America’s Cup racing has often been a test bed for design and technology that transfers to mainstream racing classes, cruising boats, and other civilian applications. But not always. Wingsails, for all their efficiencies, seem to require too much specialized handling to ever see widespread adoption, but foiling technology is another story.

“All of this board development is going to trickle into racing, big time,” Morrelli says. “We’re already stealing it and sticking it on our cruising cats. The sail-area-to-weight ratio that benefits from curved boards and angled boards and 'J'-boards, is being approached by cruising boats like our Gunboat series or our custom MM65 series on a regular basis right now. We’ve already got clients looking for us to design basically semi-lifting -- what we call lift fractions -- to start putting lift fractions onto cruising cats, big custom carbon things. That trickle is happening as we speak. We recently just stuck a set of big asymmetric canted-end foils on one of our Gunboats, escalating that war down there in the Caribbean. That’s a 62, it’s a 40,000-pound boat. So they are benefiting from some of that experience, too. The next generation of custom cruising cats will definitely get some of this stuff. For doing Antigua Race week or Heineken or Caribbean 600, you’re going to see some pretty wild 90-100-foot cruising cats flying a hull around the course in the near future.”

See California 45 at Morrelli & Melvin

Nacra 17

Want to fly your own small catamaran? Off-the shelf lifting foils may be coming soon to a beach near you. Morrelli & Melvin’s design for a 17-foot beach cat with curved foils has been adopted as a new class for the 2016 Olympics. Intended for a crew of two, the Nacra 17 has retractable curved foils to go with a high-aspect sail and a carbon rig.

“It’s really a fun boat, it’s also a boat that misbehaves,” Morrelli says. “It will pull wheelies. This boat doesn’t have 'T'-rudders, so you use your body weight and you move your body weight fore and aft to control the angle of attack, and by raising and lowering the board you get more or less surface area, so it’s a combination of board position and body weight.”

“You can get these things to nearly fly with just barely the transom touching and the leeward bow ... completely out of the water. So they are quite fast, quite active, fiberglass hulls, carbon rigs, carbon boards. They weigh about 313 pounds, and retail at about 26 grand, and you can’t get one.” At least not yet. The first 100 boats were pre-sold to the Olympic sailing teams, in sets of 10 boats, for use in their national trials.

The small boats are instructive as to the advantages of the foils. How much faster is the Nacra 17 than a similar cat, or even the larger ex-Olympic-cat, the Tornado? “[The Nacra 17] doesn’t have an advantage over anybody in light air,” Morrelli says. “In fact with the curved boards we actually give away a little bit of performance, because in light air you really want the straight super-deep boards, but at about 6 knots of wind it crosses right over to [where] the curved-board boats are faster. As soon as you can fly a hull the curved-board boats are faster, these days. Anything above 8-10 knots they’re faster downwind all the time. It’s still a close race upwind with some conventional -- what we call conventional -- cats.”

What did foils do for the SL33? “On our little test

boats, the SL33’s, the fastest we could make those go before we started putting

the foil package on was about 24 knots, because we just ran out of stability, we

ran out of righting moment” says Morrelli. “By the time we got the full package

on, those boats can go over 40. So we added 16 knots of top end to the

little boat.”

Helming: “It’s hyper“

Once an America’s Cup team made their design bets and put their boat on the water, the size, speed, and power of the large foiling cats changed the game for helmsmen, too.

“You have to be super-careful because it’s super-controllable,” Morrelli says. “You can throw the boys off back of the boat by flicking them. When you are rotating the boat about the daggerboard ... there’s no resistance.”

Getting the right sort of person on the helm was a priority, made more difficult because there was no proven pool of AC72 foiling skippers. Teams had to figure out which sailors had the skill set to excel. While Oracle Team USA’s James Spithill and ETNZ’s Dean Barker transitioned to multihulls from experience in America’s Cup Class monohulls, most of the new talent came from small high-tech dinghies, either foilers or trapeze boats that are high-velocity and physically intense.

“That’s why I think we’ve seen this really healthy transition to the 49er sailors,” Morrelli says. “Because they were born at the end of a flicking tiller, you get an innate sense of that pressure point....”

“That’s obviously where the 49er sailors came from. We’re almost transitioning, where a lot of the guys in my generation may be surpassed as we going to foiling, and this 49er crowd, the Moth crowd, is going to be the drivers of the next go around.” (See article "Big Boats + Young Sailors = Huge Opportunities" at CupInfo)

Beyond the sensitivity needed just to get the boats cranked up to speed, AC72 helmsmen must also bring the anticipation and tactical awareness to manage all that energy around the course. 40-50 knot match racing is a recalibration of the normal scale of yachting experience. Ten seconds down the race course is 600-700 feet away.

Photo:©2013 ACEA/Baluzs Gardi

“It’s more like aiming a rocket,” Morrelli says. “You’re not really sailing a boat. You are looking at targets and you are aiming. There’s no trimming going on any more. You basically set the thing and go. You grind the jibs down, they’re self-tacking. You grind them down, they are staying. And you are aiming the boat to hit the target. The only one trimmer is the wing trimmer. He’s basically trimming for twist. The things are so fast it’s only when they are whacked-up, way overpowered, that they are dumping the mainsheet.”

“It’s probably like F1,” Morrelli says. “A real good F1 driver has feeling that a normal human being doesn’t have."

There was no precedent for racing boats like these around the

buoys, and barely any for sailing boats like this at all. Nobody’s ever

really done it before and everybody’s learning.

Next Up:

With the foiling cat out of the bag, what’s going to come next for the America’s Cup? Can they go back to monohulls? There were concerns this time about some of the early races being lopsided, especially in the first-generation versus second-generation match between Luna Rossa and ETNZ. And leaders from the top of those teams on down criticized the financial and logistical demands of the big new boats, though these are complaints that have been heard around the America’s Cup in one form or another going back over a century.

“If the boats were a little more one-design next time, maybe smaller -- but even if we retain the same class of boat, the teams would be much closer together next time,” says Melvin. “This is just the first iteration, so you’re going to see some pretty large differences. I wasn’t in the America’s Cup game back in 1992, when they first introduced the America’s Cup Class, but apparently some of the races were complete blowouts at that stage as well. “

From a designer's perspective, how did the AC72 Class of 2013 turn out?

“Performance-wise, we’re extremely happy,” says Melvin. “The boats are actually quite a bit more spectacular than even we envisioned. We didn’t think they would be going this fast, but the foiling is a big part of that. Even upwind the boats are outperforming our expectations. But that’s all the development that’s gone into them – it’s hard to predict where you’re going to end up. I think that since we first launched our boat, we’re going 20 or 25 percent faster. You just don’t know where that development curve is going to end. It feels as though we’re still on the steep part; it doesn’t feel as though we’ve hit the plateau yet. So if this class were to go into the next cycle, there would still be big improvements to be made. The boats are difficult to sail, but that was part of the design brief, that they be difficult to sail. It would have been nice to have a larger fleet and closer racing, so we got part of our wish while other things didn’t materialize.”

“Whether it’s a high performance monohull or multihull, you

can still have good racing. But it may be a little hard to go back -- these

boats are so exciting.”

-- Robert Davis for CupInfo, Additional Reporting by Diane Swintal/©2013 CupInfo.com

Part 1:

Read Shaping Foils

that Re-Shaped the America's Cup with Pete Melvin (September 2013)

Additional Links of Interest:

Recommended:

More AC72 Foil Shapes, Development, and Testing with detailed photos and videos:

See Foils and Foiling Section at CupExperience

At CupInfo:

Read "Behind the Multihull Decision" with Pete Melvin at CupInfo (January 2011)

Learn more about the AC72 Class Rule at CupInfo Rules Guide

Related information:

Read more about the Nacra 17 at Cat Sailing News (March 2013)

See Morrelli & Melvin

Design & Engineering site